Malcolm Nance

I make some big claims for the power of competing truths to shape the reality of politics, climate change, economics and much else besides. But could competing truths help do what the US and other Western militaries seem unable to do: defeat and destroy Islamic State?

Malcolm Nance is an American counter-terrorism expert, a former naval officer, spy and torture-resistance instructor who became famous in 2007 for writing that “waterboarding is torture… period.” He has now published a book, Defeating ISIS, in which he argues that we should be using ideology to fight ideology, recasting how the many Muslims who support and supply Islamic State (IS) see the organization.

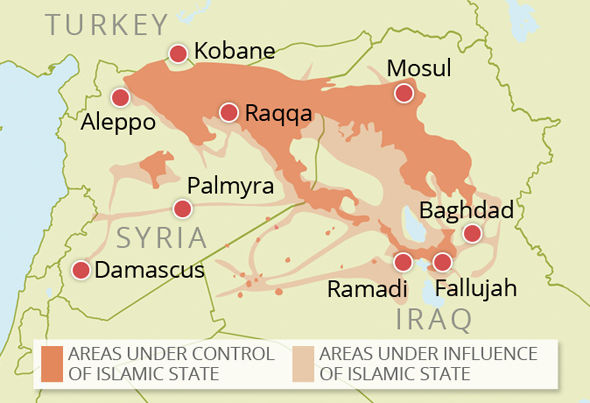

Currently, Islamic State is able to claim it really is a state because on the map of the Middle East it seems to control a large swathe of territory across northeastern Syria and northwestern Iraq:

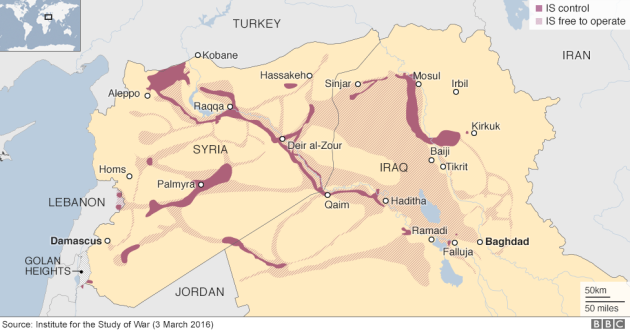

That landmass is bigger than many recognised states, and for the people who live within it, Islamic State is the unchallenged sovereign power. But in fact, as Nance points out, Islamic State really controls a “constellation” of towns and cities in otherwise largely uninhabited desert, linked by roads and other lines of communication. His point is better (but still not perfectly) illustrated in this map:

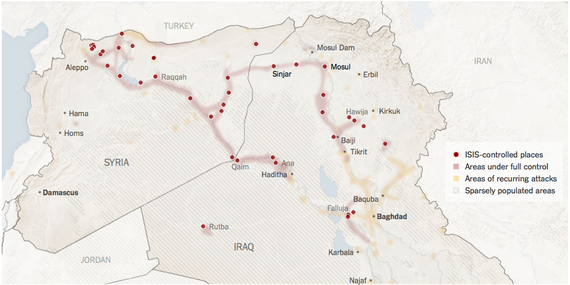

This out-of-date New York Times map may give a more accurate sense of the real IS territory:

Nance argues that we can “disrupt the narrative” of Islamic State being “this oval of a nation state that has been carved out of” Iraq and Syria, by breaking those lines of communications. He reckons this could be done by parachuting in small insurgent forces to take over particular stretches of highway; then, when IS fighters are forced to come out of the towns to combat those insurgents, using aerial bombardment to obliterate them. IS would thus be revealed to control only a string of municipalities, not a broad territory.

Having challenged the “State” part of Islamic State’s identity, Nance goes on to challenge the “Islamic” part. He sees IS not as radical Islamic extremists like Hezbollah, but as an Islamic cult. And he defines cultism as the “corruption of a mainstream religion for personal or political purposes”. He sets out numerous ways in which Islamic State doctrine departs from traditional Islam, including the practice of Takfir, the declaration that someone is an unbeliever and is no longer Muslim (with perilous consequences for that individual’s health). Nance argues that, through the “megaphone” of mainstream Islam, anti-IS forces should be broadcasting the message that “ISIS’s belief system endangers your soul” and that “having contact with them is like having contact with demons”. By challenging the Islamic credentials of IS, Nance believes, we can starve them of popular support and so undermine the foundations of their power.

The Economist last week explored a similar vein, with an article subtitled “Can the beliefs that feed terrorism be changed”? A jihadist, the writer suggests, sees the world divided into two categories of places:

- Dar al-Islam, the realm where Islam prevails

- Dar al-Harb, where the enemies of Islam are found

Under such a binary framework, the jihadist will have little qualm about attacking those not living in Dar al-Islam. But in Islam, other options exist beyond these two categories, including:

- Dar al-Dawa: the “abode of invitation”, where Islam can be freely practised even though it is not the majority faith

- Dar al-Ahd: the “abode of contract”, a place that lives in established peace with Muslims

Given these further options, the susceptible jihadist or IS sympathiser might look at the West, with its generally liberal attitude to faith and religious practice, through a quite different lens.

Both The Economist and Malcolm Nance also advocate likening Islamic State to an ancient Islamic sect, the Khawarij (meaning “the outsiders”), a group that assassinated a caliph and practised Takfir. According to Nance, members of Islamic State really hate being compared to the Khawarij – and that must be a good thing.